Holly Abbandonato, Early Stage Researcher/PhD Candidate, Science Museum of Trento and the University of Pavia, Italy

Many scientists and social scientists are becoming more and more familiar with using a holistic approach, such as integrating and understanding the ecological, economic and social values of applied research. There are two primary factors that can greatly help or hinder restoration: policy and society.

Policy and society are often foreign or unexplored fields for many scientists. As researchers, our training is in conducting experiments, analyzing and interpreting results, scientific writing, networking, and acquiring funding opportunities. Understandably, we do not tend to focus on policy or society, unless it directly impacts our research. However, in applied fields, being able to communicate our results to both policy-makers and the public can have benefits not only on our ability to obtain funding, but also to see the science put to practice. This can be an incredibly rewarding experience. Many of us who work in restoration or with native seeds know that this field has become very multidisciplinary as successful restoration is not always straightforward. Furthermore, to meet ambitious global restoration targets it is critical to find new ways to work together on common challenges that include the different disciplines and sectors.

This article is going to explore a holistic approach by examining policy and society related to restoration and the use of native seeds, and what you can do to further communicate your findings to the public and policy-makers.

Implementation of ecological restoration

According to Clewell and Aronson (2007), to be successful in ecological restoration, we need to consider the different values surrounding it, which are both independent and separated as indicated by the double solid lines in figure 1.

Figure 1. A four-quadrant model of holistic ecological restoration based on Wilbur’s generic model (Clewell and Aronson 2007).

Land management projects often involve numerous goals and disciplines. For instance, funding may be provided to a given restoration project because of the recreational value it would provide, or the natural capital or species it would protect or all of the above. Landscapes tend to have multiple values and uses. Considering them is essential for successful land management and for obtaining funding opportunities for restoration projects.

One example of a policy that did not consider these independent values was the Natura 2000 Ecological Network in Europe. It is an environmental policy that was created to implement the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 at a supranational level in Europe through the European Union’s Biodiversity Strategy to 2020. It focused primarily on the ecological values which were to restore 15% of degraded ecosystems. It was put into legislation in 1992 (92/43/EEC) and was named the habitats directive or Natura 2000 Ecological Network. However, it was protested in many European countries by fishermen, foresters, farmers and local residents who owned rural land and who were directly affected by its implementation (Keulartz 2009). The European Commission used a control and command, or top-down approach to create this directive without considering the needs of rural landowners (Keulartz 2009). This resulted in the loss of trust between policy-makers, scientists, and society.

“All of a sudden, the farm we sold our soul for to make it suitable for intensive use and to meet the increasingly severe environmental directives had been coloured yellow on the

map—the colour of future nature reserves. The arrogant way in which our right to exist was being challenged—that was the worst. We had completely lost our trust in politics.”

(Keulartz 2005; Keulartz 2009)

It can be very challenging to enforce environmental policies without considering other restoration values, especially when trying to restore privately owned land. Keulartz (2009) also mentioned that re-gaining trust from local stakeholders after the fact can be quite challenging; however, including them in the beginning can be time consuming and costly as well.

Furthermore, the need for large-scale restoration has created a market for the production of native seeds to meet this global demand. Throughout human history, seeds have been used to establish plants for food, medicine, fiber and housing. In the past century, we have begun to purposefully increase the use of seeds to re-establish wild plants in order to restore natural areas and processes (Bradshaw 1997; Muller et al. 1998).

Natural and semi-natural ecosystems with both social and economic value from Spain, Norway, and Canada: (a) farming and traditional use in Galicia, Spain (b) cultural and recreational use in Troms, Norway and, (c) forestry and aesthetic value in New Brunswick, Canada. (Photos courtesy of H. Abbandonato)

Socially, anthropologists have noted that cultural memories associated with cultivation and the properties of a seed consist of learned experiences, sensory embodiments, and social learning especially among farmers (Ellen & Platten 2011). When growing a plant in a social setting, seeds are the most convenient propagation strategy since they are easily carried in large quantities, survive under long storage regimes, and can withstand hostile micro-environments (Veteto & Skarbø 2009). Thus, seeds are easily exchanged creating a cultural mechanism for seed dispersal even among growers.

Los Lunas Plant Material Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico

Considering these values for native seed certification

For my own PhD project: Using current regulations and practices to develop a certification scheme for Europe, these values were essential to understand the complexity involved in creating a usable certification system in Europe for native seeds. After researching and discussing with other restoration and seed scientists, producers and practitioners, I could see that the majority of seed users and producers had many ideas of what certification for native seeds should be, but were not able to have a strong impact on creating or influencing the current native seed certification system in their country. After investigating the policies surrounding native seeds, I was able to realize the importance of a certification scheme to ensure seed quality, but also provide a benefit to all of its users. Otherwise native seeds would be sold uncertified which would not provide protection to buyers and sellers from negative externalities.

Seed policy originated for use in the agricultural sector to ensure transparency and truth-in-labeling in seeds sold commercially. It provides minimum quality requirements that can be repeated in a standardized product such as in a plant variety or cultivar. Varieties and cultivars are then patented and become proprietary providing a unique, standardized and profitable product. However, we know now that these types of plants are not appropriate for ecological restoration in most cases because native seeds need to maintain natural heterogeneity and genetic integrity. This major difference between native seeds and agricultural seeds needs to be communicated further to policy-makers to ensure successful restoration using certified native seeds.

To mitigate this, Marcello De Vitis and I designed a survey to understand certification and to characterize the native seed market, taking a bottom-up approach. Our aim was to try and understand the socio-ecological values and concerns that everyday users and producers face when using native seeds for restoration. We could then use this as a baseline characterization to highlight current ecological and socio-economic issues and provide future solutions to inform policy and researchers.

Reaching out to society and policy-makers

As humans we are very curious beings, yet the general public is not typically so knowledgeable of scientific terminology or results and tend to obtain much of this information from media sources (websites, TV, radio) or from educational or outreach events, which may or may not present them accurately.

Finding new and engaging ways to help the public understand not only our scientific findings, but why they are important, and how they can help to mitigate these problems can be a very promising way to provide social pressure to policy-makers to act on current ecological issues such as climate change, loss of pollinators or protecting ecosystem services and habitats.

Creating regulations can be a balancing act between economic profit and user protection. Regulations are more successful in developed markets, whereas the native seed industry is relatively small compared to the agricultural or forestry sectors. It does have the potential to grow substantially to meet the global restoration demand. Regulations that are entirely environmental, such as the habitats directive can be extremely difficult to implement without using a bottom-up or participatory approach.

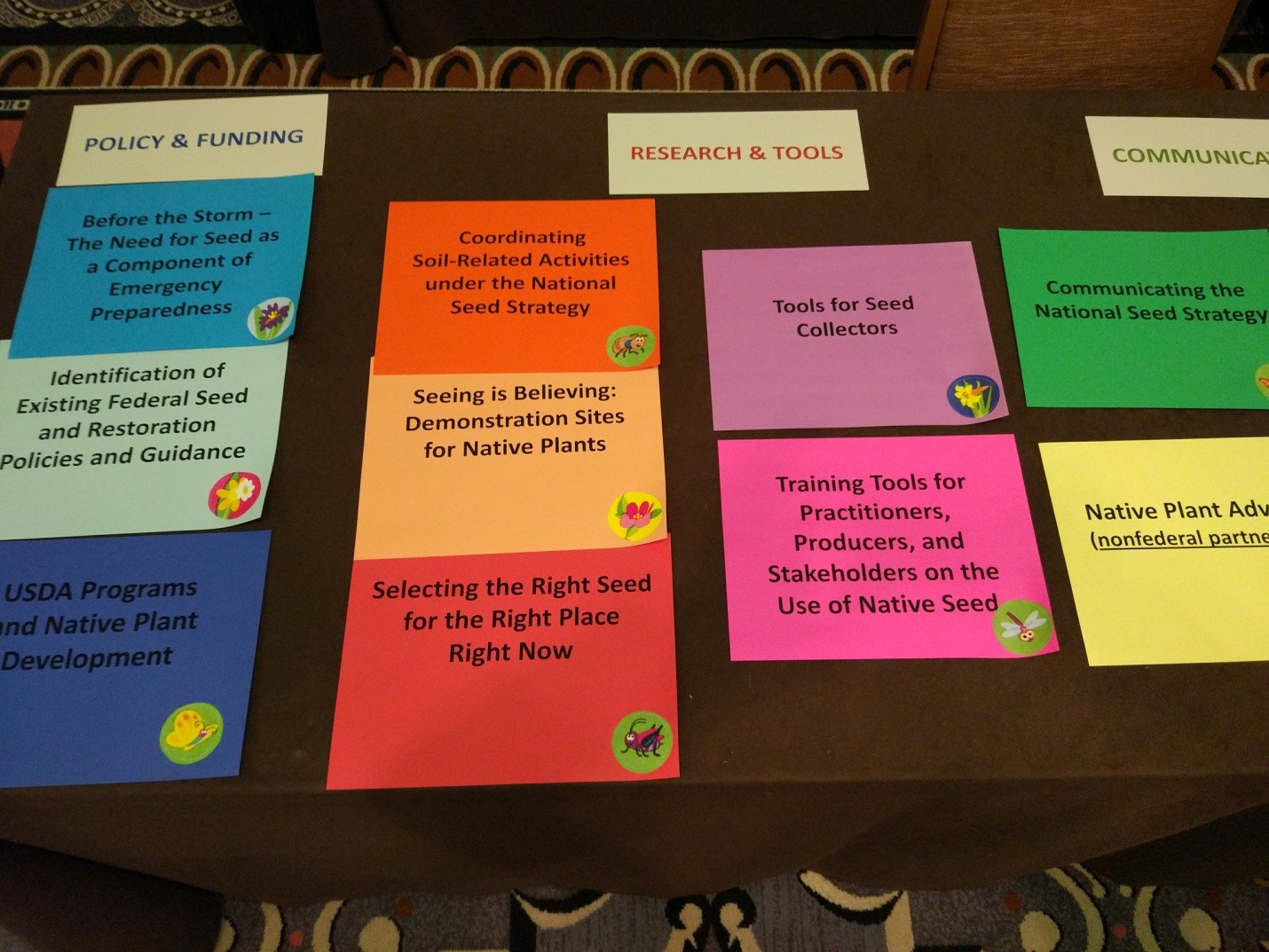

Working groups for the BLM Seeds of Success Strategy at the National Native Seed Conference in Washington, DC. Photo courtesy of H. Abbandonato

What you can do!

Consider surveying your target user or audience to include in your publication or in the presentation of your work.

Indicate the implications of your research results for practice in your publication to make it easily accessible to policy-makers and stakeholders (e.g. Restoration Ecology).

Join societies or groups where you can get involved with policy working groups.

Share your key findings using social media or websites: tweet, post, blog and share your findings with the public.

Participate in public outreach: create native flower bed displays, present to your community, teach environmental education or provide tools for teachers, etc.

Collaborate and network with your scientific colleagues and within your community.

Join SER-INSR (International Network for Seed-Based Restoration)!

References

Bradshaw A (1997) Restoration of mined lands—using natural processes. Ecol. Eng. 8:255-269

Clewell AF, Aronson J (2007) Ecological restoration principles, values, and structure of an emerging profession. Island Press. Washington, D.C.

Ellen R, Platten S (2011) The social life of seeds: The role of networks of relationships in the dispersal and cultural selection of plant germplasm. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 17:563-584

Keulartz J (2005) Werken aan de grens. Een pragmatische visie op natuuren milieu In: Boundary-work. A pragmatic perspective on nature and the environment. Damon, Budel, Poland.

Keulartz J (2009) European Nature Conservation and Restoration Policy–Problems and Perspectives. Restoration Ecology 17:446–450

Muller S, Dutoit T, Alard D, Grévilliot F (1998) Restoration and rehabilitation of species-rich grassland ecosystems in France: a review. Restoration Ecology 6:94–101

Veteto JR, Skarbø K (2009) Sowing the seeds: anthropological contributions to agrobiodiversity studies. Culture and Agriculture 31:73–87